GenAI, Open Source, and Software Stewards

Thoughts on GenAI's impact on the Software Development RoleThe adoption of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) has been remarkably rapid. Historical comparisons suggest that adoption of GenAI use in the United States is outpacing both the personal computer and the Internet. Nowhere is this trend more evident than in the field of software development. 84% of respondents in the 2025 Stack Overflow Developer Survey and 90% in the 2025 DORA Report say they use AI tools at work.

GenAI’s remarkable ability to turn natural language into working code has led many to question the future role of software developers. Industry figures such as Mark Zuckerburg and Sam Altman argue that as GenAI produces more code and humans produce less, the demand for developers will inevitably decline. NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang has stated that coding is no longer a viable career.

AI will replace mid-level engineers by 2025… Most of the repetitive and pattern-based coding will be handled entirely by AI, freeing—or displacing—human developers.

While many of these claims come from those with a financial interest in their being true, they do seem logical. When the majority of your work has been outsourced to AI, what’s left for you to do? However, I believe that GenAI will lead to an increase in demand for software developers. To understand why this counterintuitive outcome is possible, consider the rise of open-source software.

The adoption of open-source software has steadily increased over the last 25 years to the point where its usage in commercial and enterprise software projects is almost universal. In 2015, a report by Black Duck found that 35% of commercial codebases were open-source software. In 2025, those numbers had doubled, with open-source software comprising 70% of the total average codebase. A similar report by SonaType in 2024 found that 90% of all modern software applications were composed primarily of open-source software.

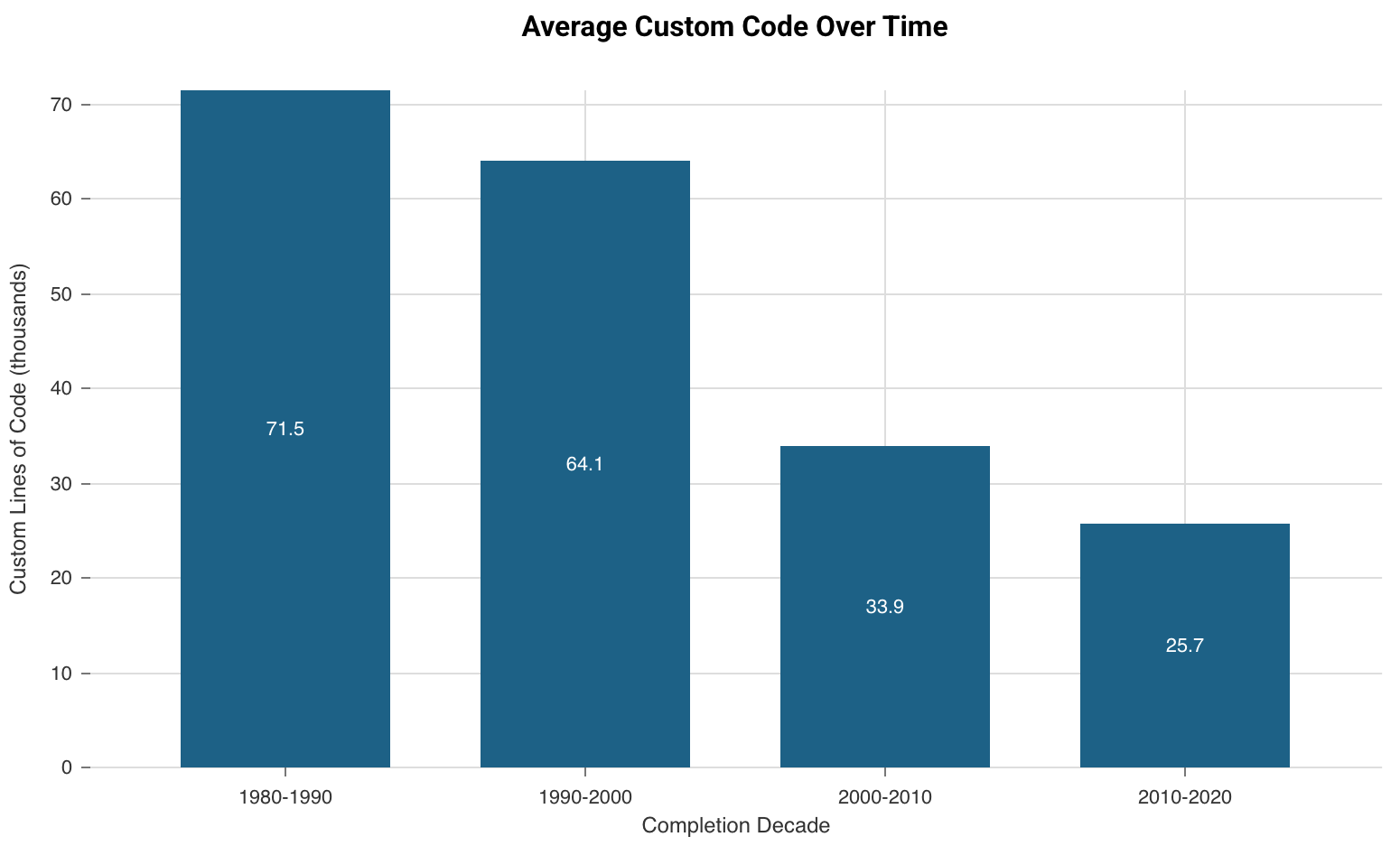

Is the amount of custom code per project actually decreasing, or are codebases simply getting larger? A long-term study by Quantitative Software Management (QSM) examined, among other things, the amount of custom code found in commercial codebases. This study included more than 14,000 software projects across multiple industries over a 45-year period and found that the amount of custom code in projects has shrunk by roughly 67%.

These studies reveal a world where software projects rely increasingly on open-source software and less on developers writing custom code. In 2011, Marc Andreessen famously declared, “Software is eating the world.” A decade later, in 2022, Joseph Jacks observed that “open source is eating software faster than software is eating the world.” If GenAI is expected to eliminate the need for developers to write code, it’s worth noting that open-source software has already done much of the work. Understanding how this shift has affected demand for software developers may offer insight into the potential impacts of GenAI.

Open source is eating software faster than software is eating the world.

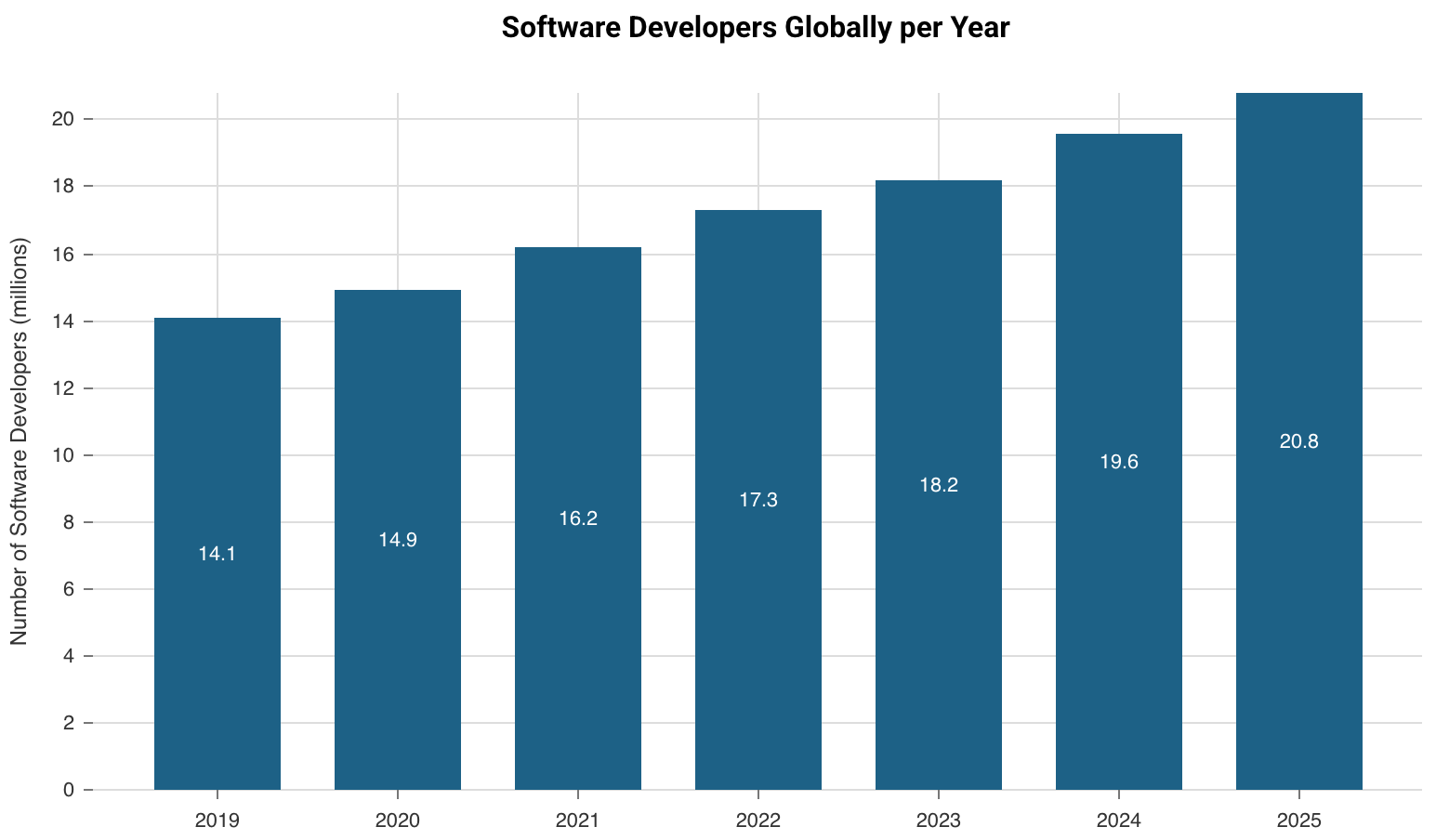

While estimates of the global developer population vary across studies, they all point to a consistent upward trend over the past decade. As software developers were writing less custom code, the overall need for them actually increased. The following chart, based on JetBrains research, illustrates the steady growth in the number of professional developers worldwide since 2019.

One explanation is that the overall software market has expanded dramatically during this period. A key driver of this growth is that open source has significantly lowered the barrier to entry for developing software-based solutions. A Harvard study of the economic value of open-source software estimated that its total value to users, measured as the cost firms would incur to build the same software internally if open source did not exist, amounts to approximately $8.8 trillion!

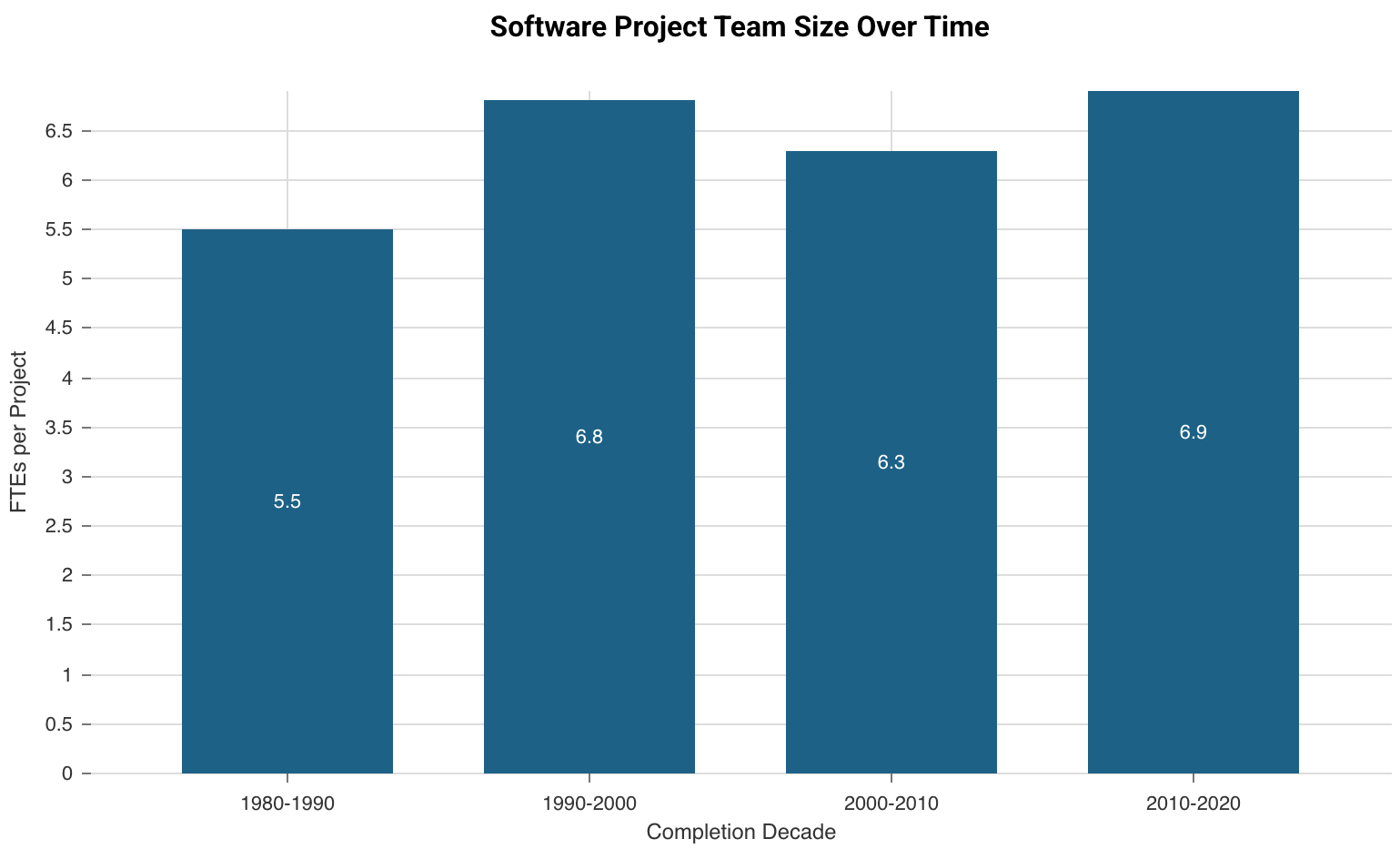

While the overall growth in the software market has naturally broadened demand for developers, what about demand at the project level? Although open-source software has made it easier for smaller teams to create and launch products, there is little evidence that long-term software projects now require significantly fewer developers than before open source became widespread. In fact, the same QSM study shows that the average team size per software project has increased slightly over the past 45 years.

I believe that the demand for software developers per project has not significantly declined, if at all, because writing code has never been the fundamental responsibility of most software developers.

It’s understandable that people view software development as being mostly, if not solely, about writing code. To many, coding appears complex and mysterious, and that perception naturally defines how they think about the profession. Nearly every term we use—developer, programmer, coder, hacker—describes the act of writing code. In many people’s minds, this xkcd comic isn’t far from reality.

Even the term “software engineer” suggests building code but describes nothing about the responsibility that follows once it exists. Yet software, in many ways, is more like a living organism than a bridge or a building. Once it is “born”, it grows, evolves, decays, and requires constant attention to stay healthy and useful. A more fitting description of what most developers do is “software steward,” emphasizing their role as caretakers who ensure that software continually performs its business purpose.

Writing code is one way this responsibility is carried out, but it is far from the only one. The following are a few other examples.

- Explaining trade-offs to stakeholders when a proposed feature could undermine the software’s purpose.

- Designing system architecture while balancing factors such as cost, simplicity, reliability, and scalability.

- Reviewing code from other team members or automation tools to help ensure security, quality, consistency, and alignment with the software’s purpose.

- Collaborating with usability, accessibility, quality assurance, security, and operations teams to understand improvements that will enhance the software’s effectiveness and resilience.

- Evaluating open source libraries, frameworks, databases, etc. to determine the best long-term fit for the project.

- Reproducing production issues to identify root causes and target corrections.

- Managing technical debt strategically by helping to decide when to refactor and when to defer based upon potential business gain vs risk.

Caring for software effectively requires a deep understanding of the software itself. This mental model goes beyond what the code “says”; it must encompass why it was designed that way, how it provides both value and risk to the business, how it’s evolved over time, and how future changes will influence its purpose. Peter Naur asserted that this mental model is the real “program” that programmers rely on, and that code and documentation are merely imperfect externalizations of it.

Open-source software has redefined the software industry by dramatically reducing the amount of code developers need to write. While this has fueled tremendous growth in the overall software market, it hasn’t significantly reduced the need for developers at the project level, because writing software is only one aspect of caring for it. The overall result has been a substantial increase in the demand for software developers.

I believe the same will happen with GenAI. It will enable smaller technical teams to build complex systems more quickly, and unlike open source, it will allow non-technical teams to create software on their own, lowering the barrier to entry even further and accelerating software market growth. But these new systems will not stay new forever. They will gain users, stakeholders, business value, business risk, technical debt, and they will evolve. These systems will need to be cared for, and that care extends beyond the limitations of simply writing code or reasoning about it only from a textual context. This is a responsibility that, I believe at least for now, will remain distinctly human.